An oft-cited piece of writing advice is to actually write. Stop thinking about writing or planning to write, and just do it. The same advice is given about hunting; you can ruminate and research all you want, but without actually trying and doing, you’ll never bag your quarry.

Easier said (or thought) than accomplished.

In the early 1990s, encyclopedias and libraries served as our (or at least mine) sources of knowledge. There was only so much research a person could do from the confines of their home before the upper threshold of information was reached. At this plateau in the investigative process, we could: halt our research, go to the library, ruminate, or actually do what we’d been thinking about.

It was more difficult than it is now to get stuck in the research phase of the investigation. Authoritative information about topics we looked up in an encyclopedia was just that: authoritative. We could still get stuck in any research phase of the process, but not for nearly as long as we can today. Through whichever screen we choose, the research potential for any topic is never-ending.

Here’s an example. At my local library, I looked up the topic “vaccine” in an encyclopedia.1

This edition of the World Book was published in 2020 and was the newest (and only) encyclopedia my local library owned.

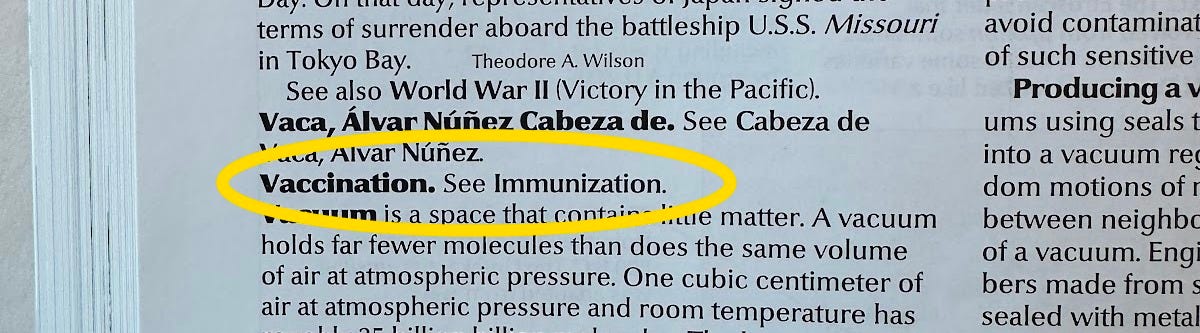

The listing for “Vaccines” redirected me to “Immunization.”

The one-page listing for “Immunizations” comprehensively laid out a definition, processes, and notable figures. This was the only page (it did not continue on the next page).

Today, in 2025, if we clear our search history and conduct a fresh Google search of the term “vaccine,” we see a variety of first page results, the first being news stories that introduce tangential concepts like “measles,” “hesitency research,” “RFK,” “CDC Considers narrowing its COVID-19 vaccine recommendations,” and Instagram stories. The first definition we see is from Wikipedia and halfway down the page we’re provided a CDC.gov listing.

These results require the researcher to decipher fact from opinion, objective from subjective. The point is that it is harder to find authoritative information than it used to be.

Is this a good or bad thing?

Pre-Internet information was limited, and if the authority was correct, then we could use the information and move on. A downside was that differing opinions and perspectives were scarce; just like history books, it’s the winners of wars who write encyclopedias. Their version of a subject becomes the truth. Today, alternatively, we face a sometimes exhausting opposite situation where, if motivated enough, it’s possible to find an argument that appears data-driven to support whatever opinion we hold.

This is my long-winded way of saying something that was iterated before the internet: we’ve entered a postmodern period of thought defined by a rejection of metanarratives (see the work of Jean François Lyotard for more about defining “postmodern”).

When we reject structures and frameworks for organizing information to the point of confusing relativity, truth becomes nuanced, undefined, and debatable. Facts become a luxury, relied upon when it's convenient (e.g., ignoring the advice of our physician until we have a heart attack, at which point the surgeon becomes our God). How can hunting help us combat this netherworld of relativity and help us regain a foothold in material reality?

Hunters face consequences. When humans hunted for food out of necessity, failing meant starving. Today, a failing hunter can drive over to Walmart after a quiet morning in their hunting blind to buy a week’s worth of groceries for less money than their latest hunting outfit likely cost them.

Alternatively, the philosopher-hunter of today (and of 200,000 years ago) adapts and keeps trying, relying not on luck, but need and skill improvement. The successful modern hunter needs to be a hunter-philosopher, someone who recognizes this activity in its contemporary context. The activity itself is the pursuit of ideas, encompassing places, strategies, techniques, and tools. What worked? What’s changed? How can I improve?

In hunting, failure is relying only on luck and never harvesting an animal.

Failure in ideas, philosophy, and research looks similar: wallowing in information, floating in the subjective, and relying on chance to provide us with bits of truth that may help us to progress, slowly, if at all.

In successful thinking and hunting, we adapt, look for new information (and are open to it), and are ready to pivot when the opportunity arises. In this sense, the philosopher-hunter is a critical thinker, distinguishing between fact and fiction while refining their ability to do so. When we hunt or think just “because” or “that’s what I’ve always thought,” we become stagnant and starving, relying on others to feed us ideas.

“In fact, the only man who truly thinks is the one who, when faced with a problem, instead of looking only straight ahead, toward what habit, tradition, the commonplace, and mental inertia would make one assume, keeps himself alert, ready to accept the fact that the solution might spring from the least foreseeable spot on the great rotundity of the horizon.

Like the hunter in the absolute outside of the countryside, the philosopher is the alert man in the absolute inside of ideas, which are also an unconquerable and dangerous jungle. As problematic a task as hunting, meditation always runs the risk of returning empty-handed.”

Ortega y Gasset, 1992, p.152

Our modern-day equivalents of the encyclopedia are Google, ChatGPT, and ad-infused news. Like the alert hunter who is ready for a quarry to appear from any direction, tuned into the sounds and smells of the forest, the philosopher-hunter does the same by looking at the conditions before them from all angles and openness, knowing the consequential outcome if they fail to do so is similarly deleterious: an atrophy of the mind that’s as consequential as starving.

*Please consider liking this post if you enjoyed it by clicking the heart (❤️) at the top and bottom of this page. Doing so will bring it to the attention of other readers.

I chose the word “vaccine” simply to illustrate how a straightforward topic can be difficult to understand in today’s information age, not to further any sort of “vaccine agenda.”

Thanks for this thoughtful piece. I’m a hunter, and can affirm that doing a hard thing with uncertain outcomes provides manifold opportunities (mostly via failure) to cultivate the “love of wisdom.” At its best, the experience of serene detachment hunting provides is, in a sense, divine. Someone once described it as standing “for a moment in the oldest silence on earth.”

The German philosopher Josef Pieper, in his “Guide to Thomas Aquinas” noted how the saint achieved the serene separation required to pen his great works. Pieper said his “cloistral seclusion became inner seclusion” and that Aquinas built a “cell for contemplation within the self to be carried about through the hurly-burly of the vita activa (active life).” That’s an apt description, I think, of hunting: a hunter needs a high level of detachment amidst the “hurly-burly” of gear, game and weather to free the mind for intense physical action. I think that’s what José Ortega y Gasset was getting at in “Meditations on Hunting.”

Herodotus noted “Of all men's miseries the bitterest is this: to know so much and to have control over nothing.” That’s the hunter’s life in a nutshell. You gather information, visualize, practice and prepare, yet it all boils down to how much control you can wrest for the serene second it takes to release the arrow or squeeze the trigger.

I once had a Great Horned Owl alight on a branch not three feet from my head while hog hunting one night in Georgia. We spent 45 minutes intently watching the same bait pile and sharing a philosophy.

This is excellent Jesse. I rarely recommend books for others to read because everyone is so strapped for time, but Byung-Chul Han's "The Transparency Society" is 45 pages long and addresses, tangentially, the exact problem you are outlining here. I'm a quarter of the way through it and it is staggering. It may help you evolve your own thinking here. Loved this piece.