Are we meant to hunt? As I journey up and down these ridges, my feet pivot below my hips on rocks, dirt, moss, fallen logs, snow, slush, mud, ice, and water. And I ponder this question.

Richard Lee and Irven DeVore’s book, Man the Hunter, presented ethnographic findings that challenged conventional thinking of the day regarding human existence pre-agriculture. Drawing from fifteen months of fieldwork between 1963 and 1965, the authors posited that “the hunter-gatherer subsistence base is at least routine and reliable and at best surprisingly abundant.” Lee concluded that in subsistence communities, though hunting isn’t generally the primary source of food, it is a critical part of the diet, which is combined with foraging, fishing and shellfishing. He estimated that “all societies at all latitudes derive at least 20 per cent of their diet from hunting of mammals.”

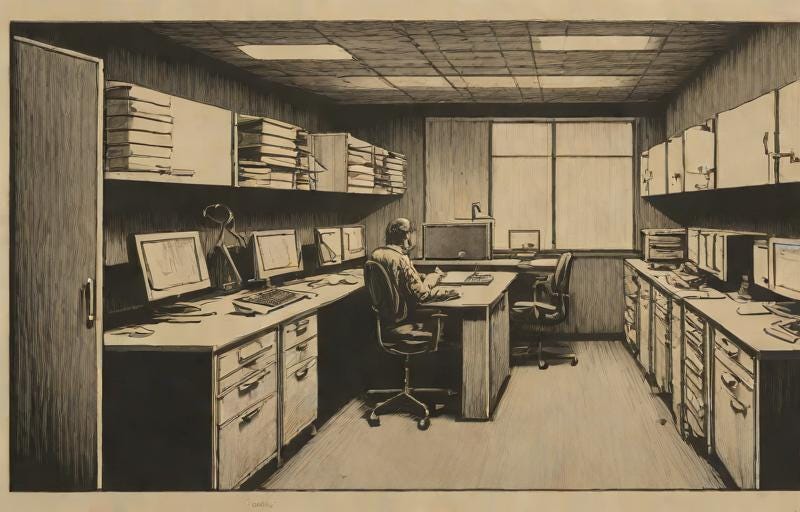

Think about that: humans engaged in hunting and gathering as a way of life for a couple of million years prior to the relatively recent technology we call agriculture, developed only ten thousand years ago. Assuming modern examples of hunter-gatherer communities broadly represent what life was like during the Pleistocene (that 2.5 million-year period before agriculture), Lee’s research re-casts this time period as less harsh than most people assume. Communities not only ate well, relying on a plant and animal diet, but they generally didn’t live in a constant state of struggle. Fast-forward to the modern and increasingly urbanized world, it’s no wonder we sometimes feel out of place staring at a computer screen all day.

“All major human characteristics – size, metabolism, sexual and reproductive behavior, intuition, intelligence – had come into existence and were oriented to the hunting life.”

Humans have hunted for a long time; longer than we’ve been farming or living in cities. In fact, Paul Shepard argues that farming is largely responsible for most of the ills we face in modern living. Social, psychological, and physical problems emerged and intensified as a result of the efficiencies humans gained from agriculture. Ninety-nine percent of human time on earth has been spent living a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In fact, Shepard goes so far as to declare we are “people of the Pleistocene.” Some farming advocates argue that agriculture yielded a plethora of societal improvements, such as increased leisure time, but this simply isn’t true. Pre-agriculture people didn’t starve, work all the time, or die young.

Cal Newport provides insight into present-day work environments in the context of our hunter-gatherer history. Speaking to the frustrations of countless knowledge workers, he reifies the incongruity between our brains and cubicle life:

A mind adapted over hundreds of thousands of years for the pursuit of singular goals, tackled one at a time, often with clear feedback about each activity's success or failure, might struggle when faced instead with an in-box overflowing with messages connected to dozens of unrelated projects. We spent most of our history in the immediate-return economy of the hunter-gatherer. We shouldn't be surprised to find ourselves exhausted by the ambiguously rewarded hyper-parallelism that defines so much of contemporary knowledge work.

Cal Newport, New Yorker, 11/2/2022

What Newport terms “fragmented mediocrity,” is the type of busyness that’s all too familiar to many of us, especially in the post-pandemic era of Zoom meetings and Microsoft Teams. Most employed people I know who sit in front of a computer all day are leading stressful, busy, and fragmented lives where their attention is constantly split between innumerable tasks. This shallow work environment culminates in workers who are chronically stressed, overworked, and unsatisfied. Simple, straightforward projects take longer than they should, and sustained concentration on an assignment is nearly impossible.

Email, virtual meetings, and chat make it easier to fragment your own day as well as other’s. General dissatisfaction is attributable not only to this multitasking work environment but to the long-term nature of the work product. A new piece of software or electric car prototype cannot be designed in a day. Complex inventions of the Information Age require daily work that doesn’t appear fruitful on a daily cadence. If your week’s conclusion is marked by the number of emails sent or spreadsheets updated, there really isn’t any material reality you can see or touch to get excited about. In this regard, a sense of disillusionment becomes understandable if your primary task is to organize electrons and then watch them vanish as your laptop snaps shut. Our ancestor’s day-to-day grind had a huge perk; whether it was a single or multi-day hunt or harvest, they had something to show for their efforts.

Sprinting up through the gun smoke to where the deer had been standing, there were dark red spots on the snow. I thought to myself, “Good, there’s blood. Contact.” Adrenalin pumping, I ran after the injured buck, caught up with him, and finished him off with another shot into the vitals. I moved fluidly and, without friction, concentrated on this single task: kill the deer.

...I will say this to further though. Farming with draft horses as opposed to machines (meh) is pretty sublime. I literally never get used to how magnificent my horses are, it awes me every single day. The life is a consolation prize for sure, but a pretty good one for its evils. For me, some hybrid of subsistence farming and hunting, deep in some range of hills, would be the ultimate. The lives of the Iroquois, the Metis, the Appalachian mountaineers prior to the railroad. Perhaps the best of all worlds?

Amen to all this. "Fragmented mediocrity" indeed. Or, just as aptly in my observation, frantic mediocrity. I've begun my spring bear hunts, yesterday. Nothing is more real nor fabulous than being out in hills after bear, aside from other versions of this involving equally galvanizing quarry.

I think i may have mentioned, you must read Herne's "White Hunters" if you have not. Such fabulous - and not infrequently short - lives illuminated here. It's not just a celebration of living the genome, but a withering indictment by comparison of indeed just how mediocre - and just how truly shockingly dull - modern existence is for most. Isn't it perverse to witness just how much of our day, our attentions, our lives, we devote to producing an experiential nothingness today?