Finding Solace and Strength on Vermont's Long Trail

Embracing Impulse and Finding Peace in Wild Places

Autopilot for My Mind

As a child, I hiked portions of the Long Trail that overlapped with well-known ascents, like Sunset Ridge and Forest City trails. Liberated, I could run ahead or fall behind, and it didn’t matter; the trail was there, a guide, a worn path that physically challenged me, and my mind could take a break. Eventually, I imagined hiking as a form of autopilot or mental cruise control.

I was a seven-year-old kid sprinting down a gnarly section of a narrow trail, leaping over rocks and roots, falling, and getting scraped by spruce branches. The trail was my “happy place,” and I was engaged. Unlike the classroom, where stillness suffocated me, the trail set my mind on a natural ‘autopilot,’ allowing me to focus on each step without distraction. Come Monday, I sat in an over-heated carpeted classroom and listened to a teacher drone on about long division. It felt impossible to be there as I fell asleep, made jokes, passed notes, and irritated my teachers.

I wanted to feel normal, and the only way I could do this was by being outside, mainly in the woods. A soccer or baseball field didn’t cut it; that was just another version of a classroom, with rules and plays to remember.

We drove home from those childhood hikes on Interstate 89, a highly traveled road in Vermont. You can see an entrenched groove in the pavement from the tires of countless vehicles that travel the same length over and over. The pavement chewed away from all that spinning hot rubber, a slow-motion excavation. Sometimes, they’re prominent enough to jerk the car to the side, forcing all four wheels into place. I sometimes wondered if a driver just let go of the wheel and let the car drive itself in those parallel channels, coasting along, cognitive load freed up to daydream.

Finding My Groove: Hiking as a Teenager on the Long Trail

In early August of 1999, a friend and I devised a plan to hike the most challenging section of Vermont’s Long Trail as a summer finale before college. Hastily executed, our attitude was, frankly, “fuck it.” Our unplanned trip, full of impulse and empty of structure, might have seemed reckless—but for me, it was the exact mental reset I needed. A friend dropped us off at the trailhead in Hanksville, and we started the 105-mile journey. Invincible, we didn’t think twice about the mileage we planned to cover on a five-night trip. Twenty-one miles a day was a lot, and that was the point. Challenge ourselves, see what happens, don’t overthink it.

At this point in our lives, the outdoors was essential to each of us. It represented classical ideals of “nature” and the “environment”; it was beautiful to look at and experience. Protect it. We needed to “save” it. These nebulous conceptions that I couldn’t articulate beyond the headline but still felt passionate about. I hadn't considered why I gravitated towards places like the Long Trail.

We arrived at Cowles Cove Shelter, the wind ripping at our backs. While valleys might be hot and rainless, up high, mist crept through the softwood trees, kept us cool, but soaked us at the same time. Lugged sole leather hikers picked up mud, like food sticking to an ungreased skillet. There were long sections of silence with equally long sections of discussion about college, speculation about the next water source, or whether we should eat the chocolate now or save it for later.

As we hiked up and down the northern half of the backbone of Vermont, unplanned adventures crept up on us. We took a detour to downtown Johnson, where the Lamoille River’s steady current washed away three days’ worth of grime. Around the corner, we filled our stomachs with Mobil gas station hot dogs. Then, we cheated and bypassed a section of the trail by hitching a ride with a long-haul eighteen-wheeler.

Shooting stars sped through a midnight blue clear sky that night, and we smoked pot with strangers in the shelter from the comfort of our hand-me-down sleeping bags. Waking up the following day to a blazing sun on our dry, weatherbeaten faces, the impulse to move from a place of comfort took hold, and we were back on the move. Gear on our back and the initial soreness of raw blisters and pummeled thighs in the rearview mirror, we settled into our hiking groove, like those parrel lines in interstate pavement.

Embracing Impulsivity

Unintentionally, hiking in extremes and our “fuck it” mentality persisted and became a pattern as we got older: Step 1: find a unique area to explore, Step 2: plan a hiking trip that involves an excessive amount of miles, and Step 3: hike and see what happens. We prepared by packing food and the appropriate gear, yet we never looked at the weather or gave anyone specific instructions on where to find us.

Our impulsivity led us to North Cascades National Park and Thailand, and our hikes became more spontaneous, almost as if uncertainty were required. This compulsion to leap into the unknown wasn’t just thrill-seeking—it was relief from the structure I always found stifling. Today, as a parent of teenagers, I look back at us and think, “That was stupid.” I imagine asking my kids, “What’s your plan?” if they shared ambitions for a similar adventure.

Cliched notions of hiking as therapy or the outdoors as one’s “church” are not in short supply. As an eighteen-year-old, the concept of therapy wasn’t even on my radar; I wasn’t mindful or reflective. I was pure impulse; all gut, no brain. Yet these extremes scratched a mental itch, a physical struggle that harnessed my mind, combined with the beauty of the natural world—one step after the other, legs throbbing, walking in silence. Soaking wet from the rain or overheating, our shoulders rubbed raw, and ankle blisters nearly down to the bone. Distractions that pass the time and that prevent the neuroses of thinking about the boring topics of school.

We have well-worn paths in our minds: habits, comfortable spaces, things, or activities that grab us. These mental paths define me, my tracks, and my relationships. I’ve realized that these paths need following; they exist so I can sleep at night, like a dog that needs a walk. When you arrive at the front door, the owner holds the beast back on its leash. “He’s friendly but just gets a little excited,” as the dog jumps, scratches and licks, wishing to be released.

New Perspective

It was oddly comforting to have a name for the impulses that had shaped my life, but taking medication brought on a clash I wasn’t expecting. At first, I thought back to middle school behavioral problems and why high school felt so confined. An “Aha” moment, I thought back to when I was plopped down on that blue plastic molded chair, wondering what was wrong with me while the teacher explained how to “divide by the divisor, find the remainder,” etc. I now knew the issue, and I had a “solution” literally in the palm of my hand.

Adderal focused my mind in a particular way, forcing and bending my brain to remain stationary and concentrated. I felt horrible, though. Here was a drug that tricked my brain into thinking it was okay to sit at a desk for eight hours straight! I may be numb to it in the moment, but the result was, for lack of a better word, “ickiness”; my body was telling me I would still suffer the consequences of silencing it. This realization was a low point; now I knew what it felt like to be “normal” and how it was feasible to sit in a classroom, but my body hated the drugs.

I have a proclivity for finding the edges of experiences, the antipodes of outdoor adventures, a desire to go further and higher. These pursuits provided an in-the-moment-ness, and I couldn’t get it any other way. What if I received medication as a child? What would have been different? Better grades? Different friends? Would I still be intimately reliant upon all things outdoors for my groundedness? Could I have held a “regular” job for over a year?

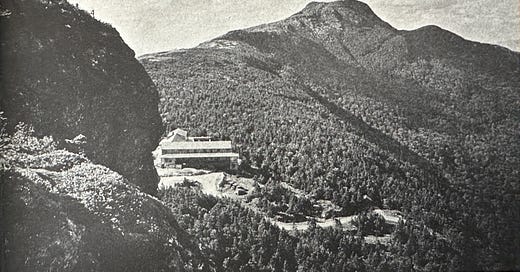

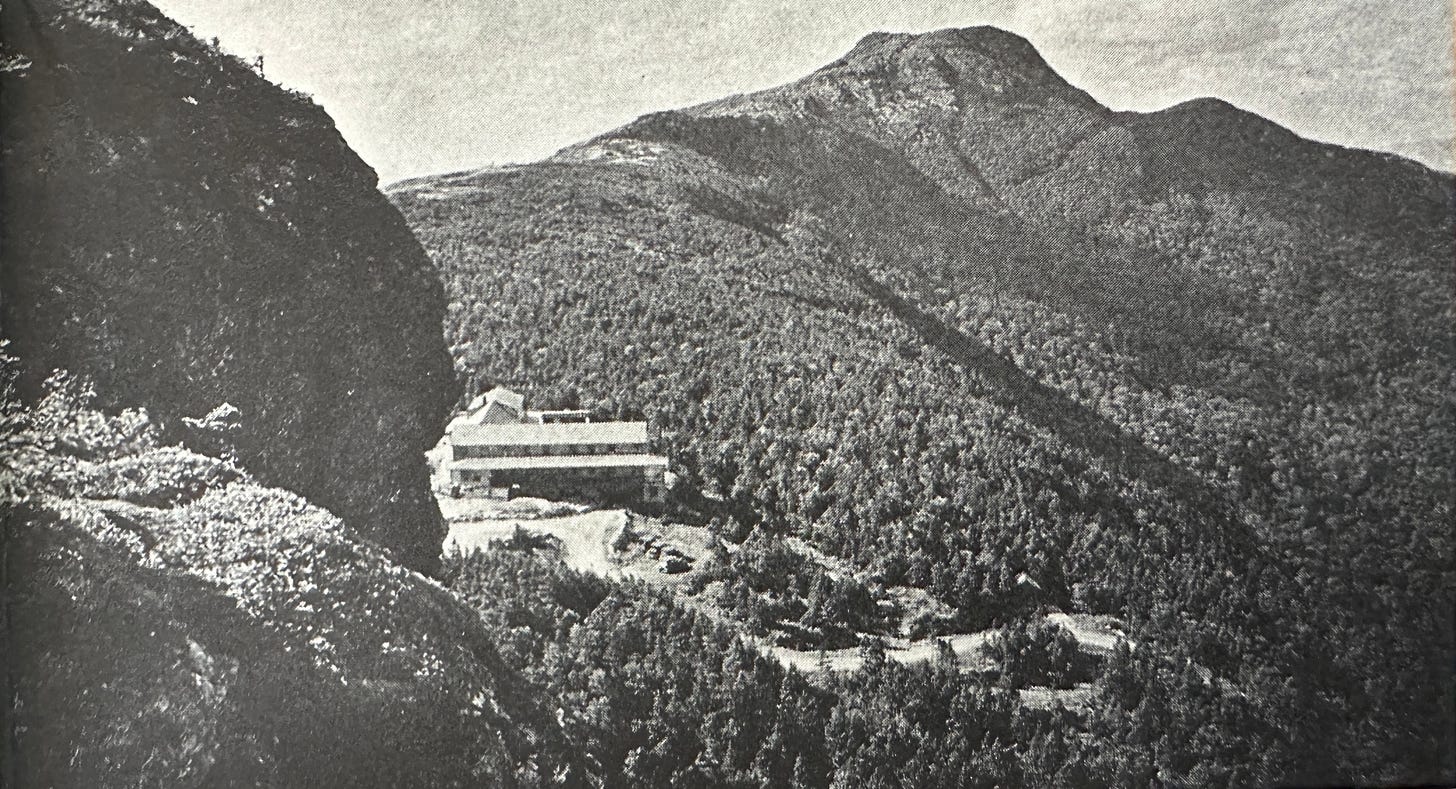

It’s no coincidence I now live within walking distance of the Long Trail. It’s surprising to think about it when you consider all of the twists and turns of life that happen between high school and middle age with children. Within minutes, I can be hiking the same ground we traversed that summer: granite and dirt underfoot, spruce in the air, connected to the rest of the state through this 273-mile artery.

Choosing Nature Over Medication

The Long Trail is a powerful vehicle for outdoor conservation. Since 1986, the Green Mountain Club has permanently conserved most of the trail and its adjacent unprotected lands. In total, 25,000 acres have been conserved by the GMC, thereby guaranteeing access to this vanguard resource of the state. Light green beech leaves flutter while the smell of spruce fills the air as you ascend the trail; it’s not unlike other “long” trails throughout the US, with familiar species inhabiting different sections, reminders of a particular bioregion.

I still appreciate the environment for the solace, the trees, and the smells, as I did as a senior in high school. Yet my perspective has shifted and deepened; the outdoors isn’t just a scenic escape. For me, it’s been a place to channel impulses and engage. In this sense, the physical reality of the Long Trail (and the efforts that have manifested for its creation and conservation) is reflexively tied to my mental reality.

Would the Long Trail even exist if early trail builders could have medicated their way through the itch to move, explore, see mountains, and build shelters? Would the trail instead turn into a “scenic road,” fragmented into an island of shopping opportunities for motorists to “take in” the top of Vermont, thereby denying future naive teenagers from planning overambitious hikes?

What’s unique about the Long Trail is that it serves as an emotional sponge. As a child, it absorbed my energy as I ran ahead and fell behind. As a teenager, it soaked up my impulsivity. As an adult, it provides a challenge, a place of context, and a vital choice: should I take a pill or go for a hike? The impulse is there for a reason; to deny it would be to deny the wilderness, adventure, and friendship.

*One of the best things you can do to support this writing is press the heart button (❤️) at the top and bottom of this page if you like this essay. Doing so will bring it to the attention of other readers.

Great writing, Jesse! Really valuable thoughts about our true nature, the failures of modern schooling, and ADHD/medication.

If you haven't come across it already, I think you would really enjoy Thom Hartmann's book "ADHD: A hunter in a farmer's world" that takes an evolutionary view of behaviors that were highly adaptive until we created our "modern" industrial world. He has a Substack that explores those ideas in depth:

https://www.hunterinafarmersworld.com/

What a great perspective! I can really identify with those feelings of restlessness, and did my share of almost reckless solo backpacking trips as a teenager long before cell phones or GPS or emergency beacons! Its different now. Hard to re-capture that feeling of total freedom.