Fifty Blue Eyes

Reaping where you do not sow

The Takeaway:

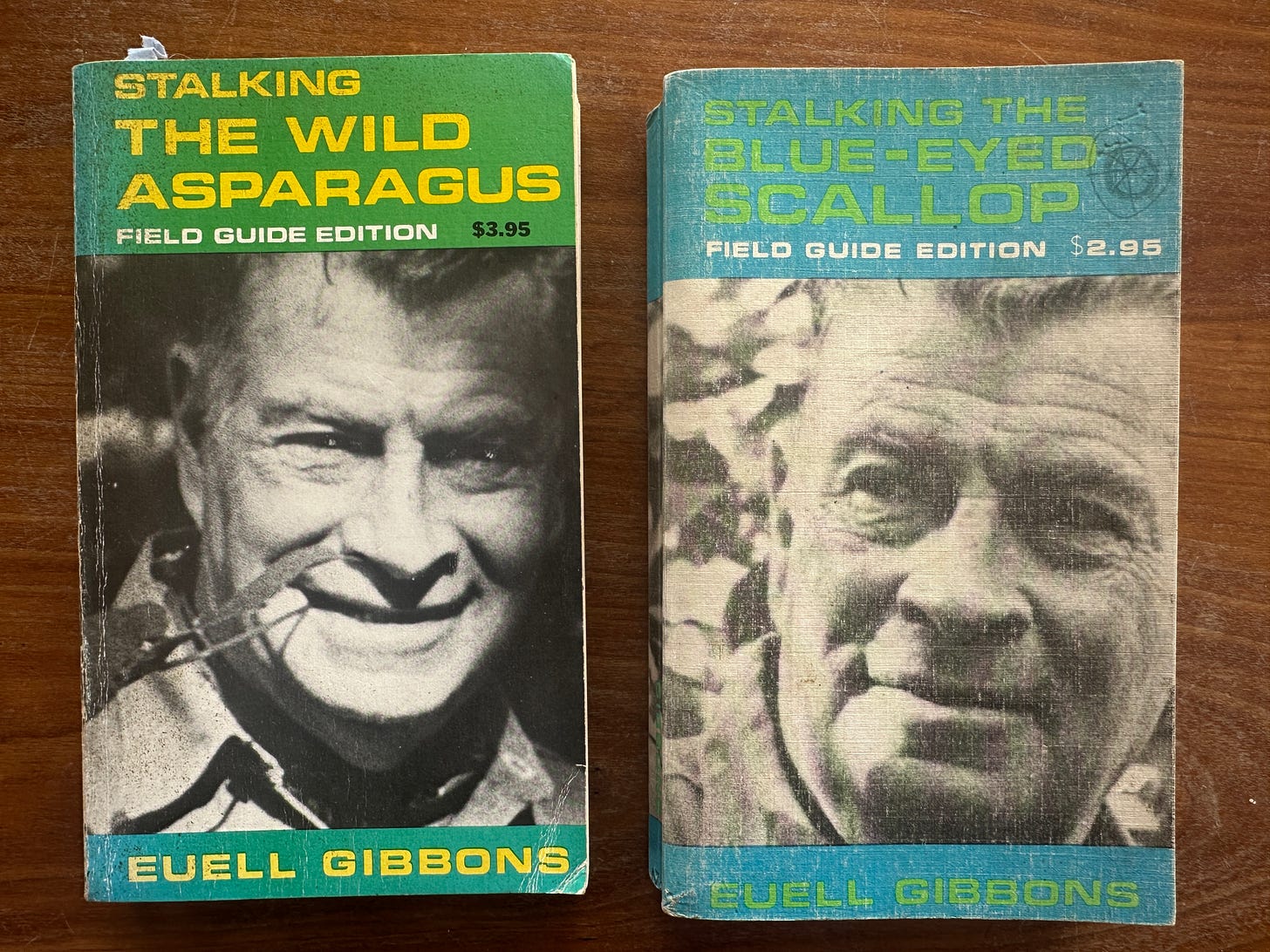

Euell Gibbons, a forager and writer who gained notoriety in the 1960s.

Next week: Books about food…

With the judicious, if incongruous, use of a home freezer, he could stay fat the year round by “reaping where he did not sow.”1

Fifty blue eyes wobbled through the lagoon water, skipping over rocks, resting on sand, and darting by minnows. Scallops swim. They don’t burrow. They race backward; their top and bottom shells flutter open-shut, in propulsion, their hinge facing forward, in the direction I assume they want to go. Those fifty eyes are looking at the rearview.

Euell Gibbons was born in 1911. He lived close to the land, foraging for survival from a young age and later achieving fame for his two well-known books: Stalking the Wild Asparagus in 1962 and Stalking the Blue-Eyed Scallop in 1964. Settling in Pennsylvania, Gibbons was a pioneer; he wasn’t a survivalist but a food system thinker and chef whose philosophy was practically-minded, utilizing the everyday plants and animals around him. If we apply his philosophy today, we’ll realize not only Gibbons’ prescience but the contemporary need to apply his spirited worldview to epicurean concerns and beyond.

Gibbons’ matter-of-fact writing shows how out-of-touch social media has made us. To live and not talk and advertise it, or do it solely to promote ourselves, is rare. A nonchalant killing of a woodchuck or porcupine because of a lack of luck on a mule hunting trip for Gibbons was no big deal. In this way, his lyrical writing about nature comes close to paralleling Leopold’s.

Foraging in the Convenience Age

When re-reading his books, I’m inspired but disappointed in how incompetent I am in my ambitions compared to Gibbons’; his weekends away with friends where he constructed every meal from foraged foods and even canned some to bring home. It is hard to know the reality; was Euell a cranky fellow on those weekends, miserable to be around because he was exhausted looking for dandelion roots and cattails? I doubt it since he kept doing it, hosting wild parties for friends.

Wild foraging is hard work. I’ve tried several Gibbons’ recipes, but usually only once.

A Foraging Revolutionary

Sixty years after publication, his introductory words in Stalking the Wild Asparagus resonate today:

We live in a vastly complex society which has been able to provide us with a multitude of material things…but people are beginning to suspect that we have paid a high spiritual price for our plenty. Each person would like to feel that he is an entity, a separate individual capable of independent existence, and this is hard to believe when everything that we eat, wear, live in, drive, use or handle has required the cooperative effort of literally millions of people to produce, process, transport, and, eventually, distribute to our hands. [p.1]

After staying up late roasting dandelion roots and making dewberry jelly, Gibbons woke up the next day to collect bullfrogs, crayfish, and black raspberries for the upcoming round of meals. One April feast he made for his guests assimilated the following wild-foraged ingredients: wild leek soup, chicory, daylilies, calamus stalks, crayfish tails, wild onions, dandelion crowns, cattail root flour, chokecherry, Japanese knotweed, and wild ginger.

All Consuming Passion

Consider another excerpt from Stalking the Wild Asparagus where Gibbons described the complete self-sufficient in the average places we encounter regularly in our urban, rural, and suburban environs:

One doesn’t need to go to the mountains or virgin forests to find wild food plants. In fact, mountains and dense forests are among the poorer places to look. Abandoned farmsteads, old fields, fence rows, burned off areas, roadsides, along streams, woodlots, around farm ponds, swampy areas and even vacant lots are the finest foraging areas…I have collected fifteen species that could be used for food on a vacant lot right in Chicago. [p.3-4]

Deep down, Gibbons’ appeal is about independence, freedom, and the ability to be self-sufficient with very little. What a great counterweight to the current moment where buying something and asking permission is frequently a prerequisite of doing.

The manner in which Gibbons pursued his foraging passion was all-consuming—in a good way. A long weekend with friends where the entire day’s activity focuses on foraging in unfamiliar forest and field—where you’ll venture, what (if anything) you’ll find—is alluring because of the wholehearted commitment to an activity, an unfragmented experience. There was no life paralysis2 or screentime struggles in his pursuit of wild rice and wintercress.

Flavor in My Pocket

The scallops trembled in the frying pan. As color television was to its black and white predecessor, these bivalves delivered irrealisable flavor and perception. When I ate them, I no longer imagined a heaping pile of scallops in a supermarket display case, a sanitary mausoleum of ocean bounty. Instead, I was transported face to face with fifty blue eyes, a fluttering scalloped shell, and the sensation of those ridges on my fingertips as they slid into my pocket.

Further Reading:

p. 2 of Stalking the Wild Asparagus. Gibbons is referencing the Bible, Matthew 25:24.

A concept popularized by Brené Brown in The Gifts of Imperfection.

Jesse, Thank you for bringing Euell Gibbons back to our attention. At the time, his works were pivotal in helping us to step away from the Establishment during the Vietnam War and forage freely.

From what I recall, Euell got into foraging out of necessity to feed his mother and siblings after his father left or passed away. John McPhee went afield with him. He has a great essay called Forager in one of his collections from the New Yorker, but you probably already know of it. It's one of my favorites. They hit the AT with no food for many days. Have you read McPhee's Survival of the Bark Canoe?