Incidental Catch

He slapped the surface, reminding me of the sound of an irritated beaver’s tail. The unidentified creature and I are in a heightened bout of tug-of-war. An onlooker says, “I think it’s a ray or skate.”

I ignore him and focus on the yellow line that disappears in the water, slicing back and forth a seawater bandsaw with working motors at each end.

Identifying the Bullnose Ray

The Cownose Ray can jump out of the water, crush hard-shell mollusks with tooth plates, and congregate in schools of up to 10,000 fish. That’s the fish I thought I caught. But after researching it further and confirming with folks at the New England Aquarium, I actually landed a Bullnose Ray. They look similar to a Cownose, but the Bullnose has a subtle duckbill-like snout and spots.

Growing up to 33” in wingspan, this one was close to that size. I estimated it weighed 40-50 pounds. A type of stingray, they are common in the Atlantic Ocean.

Eerie and magnificent, the stingray looks both space-age and middle-aged. Face-to-face with it on the beach, I was mesmerized by its flapping wings and expressive eyes. I had no idea what type of ray it was at the time, but I did notice its smacking tail and, with relief, realized the circle hook was in the perfect location for removal in the side of its mouth.

Ancient Human Fascination with Stingrays

I’m not alone in my captivation with the stingray. In 2018, researchers found a sculpture of a stingray on the coast of South Africa, dating its creation to 130,000 years ago, a significant timeline since this predates all previously discovered figurative art by thousands of years, upending our understanding of the human creation of figurative art. In this case, the sculpture is probably a testament to humans’ regard for this fish as food and something to fear.

Did I fear it? Yes, its tail flapped up and down as I worked the hook out. Did I want to eat it? No, since I hadn’t prepared to catch it, nor did I know the legality of harvesting a ray.

The Function of Spiracles

The spiracles on this fella were huge. In case you don’t know what they are, spiracles are the holes near the eyes that allow rays to breathe while buried in the sand. While sandy water gets sucked in through the gills (located on the bottom of the ray), clear water gets drawn in through the spiracles. A considerable advantage in mother nature’s game of hide-and-seek is that a ray can hide but still breathe, like a sand snorkel, except better camouflaged.

Shagreen: The Many Uses of Stingray Leather

A couple of weeks after I caught it, I told a friend at a wedding about this catch, and he mentioned that artisans in Japan use stingray skin for knife handles. Curious, I went down the research rabbit hole to learn about shagreen and its various uses.

Leather enthusiasts can easily find stingray leather in stingray farms in Southeast Asia, where black diamond stingrays are grown for leather and food. One can order stingray leather, purses, wallets, and belts online. Wild-caught Bullnose Stingray is eaten in Central America and caught with longlines and trammel nets.

In the Atlantic coastal waters of the US, they’re usually not targeted by fishermen but often as bycatch of recreational and commercial fishing (e.g., trawling, seining).

In the Indo-Pacific, people harvest wild-caught stingrays for meat and leather: the wings for meat and the dorsal skin for leather. One percent of the world’s leather comes from exotic sources such as stingrays. Shagreen (the name for stingray and shark leather) is desirable for its high tensile strength. Whether you’re looking for a samurai sword handle or a wallet made of stingray, it’s likely just a few mouse clicks away.

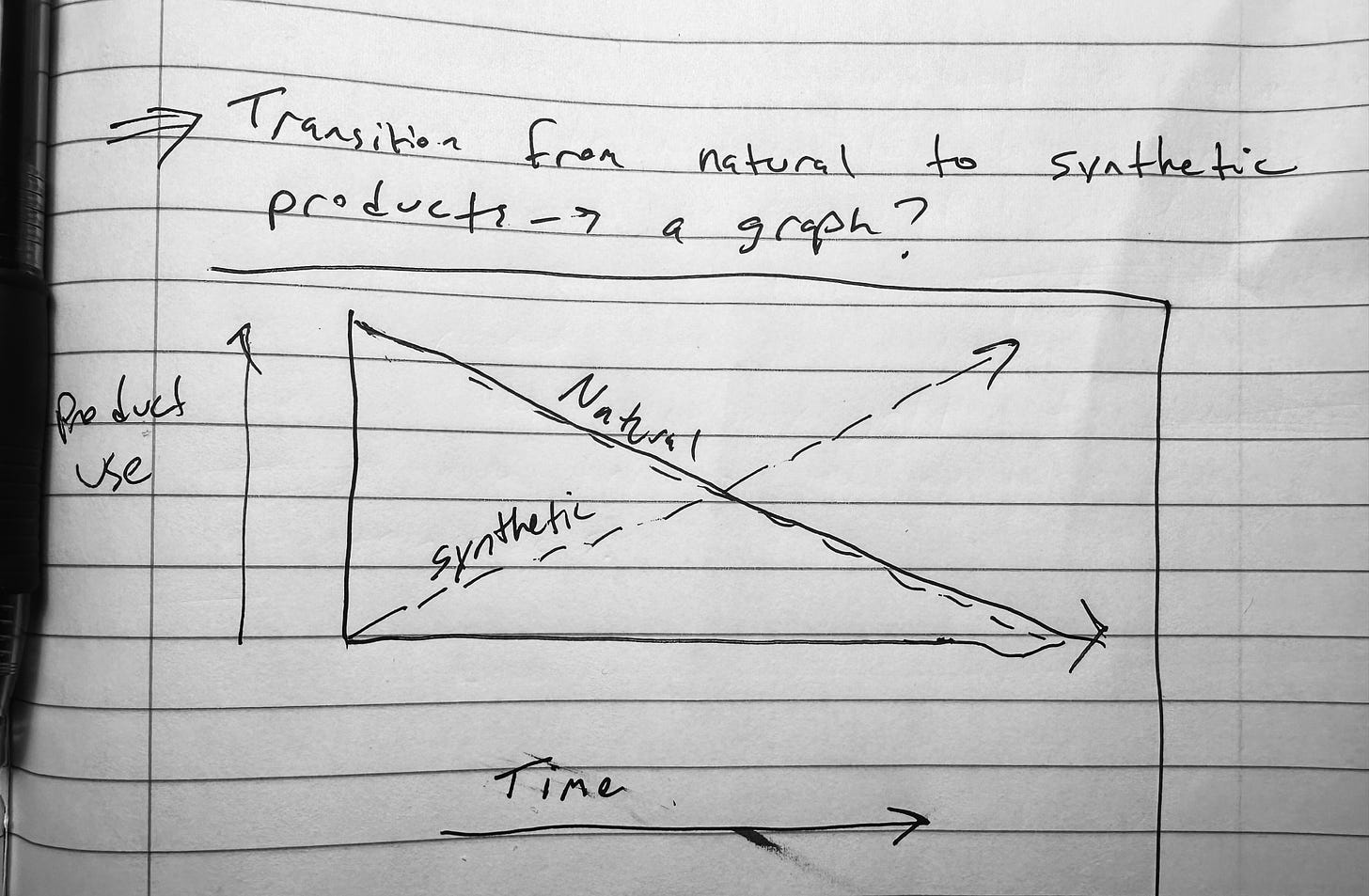

That day on the beach, there was no leather, let alone shagreen. Plastics are responsible for my fishing rod, cooler, shorts, sun shirt, sunglasses, and water bottle. It’s also responsible for the beach trash encountered by anyone who strolls down an unmaintained coastline anywhere on the globe.

From Ivory to Innovation: Plastics, Leather, and the Human Footprint

"It is conceivable that plastics may one day become a dominant material, just as steel did in the immediate past. Or, to put it more strictly (since there are so many kinds of plastics for so many purposes), they may become dominant as metals in general have been dominant from times remote.”

- Plastics Come of Age, p.301, Harper's Magazine, 1942, Vol.185

The first synthetic polymers (e.g., cotton cellulose treated with camphor) were developed in 1869 by John Wesley Hyatt; the motivation for this disruptive creation was alleviating the strain on the ivory supply chain induced by billiards. In 1907, the development of fully synthetic plastics (e.g., containing no molecules found in nature) accelerated an age of unstoppable potential: reliance upon natural resources like wood, leather, and aluminum was a thing of the past.

At no time has the substitution of natural for synthetic been more pronounced than at the onset of World War II when natural resource constraints accentuated the need for a seemingly limitless substitute (in this case, plastics).

And it does seem limitless. So far this morning, I’ve touched a keyboard, pen, screen, phone, truck, and toothbrush: all are plastic or need plastic to function.

Thinking back to the beach that day, perhaps my sneakers in the truck contained leather?

Speaking of sneakers, footwear uses fifty-four percent of all leather produced on Earth. The US consumes the most footwear globally: eight pairs of shoes per capita (the EU is second with 4.2 pairs per capita).1

The “cotton” pants I'm wearing contain three percent spandex for "extra flex."

Joseph Shivers Jr. of Dupont invented spandex in 1958; Dupont sold the spandex-producing part of their business to Koch Industries for $4.4 billion in 2004.2

But the belt holding up my pants is made of leather, likely that of a cow (bovine leather comprises 66 percent of global raw leather— next is sheep (15%), pig (11%), goat (7%), then “other” (1%).

Recognition and Return

I popped out the circle hook and looked into the ray’s eyes and spiracles. They draw me in like a friendly dog’s eyes who is rubbing against your knee while glancing up at you. In this case, it’s a portentous and deep stare, and there’s a heaviness in my gut telling me this thing is out of place—the northern end of its range, on the sand, out of the water.

Too heavy to move alone, the onlooker helps me turn the ray around and push it back into the surf. Quickly and quietly disappearing below the water’s surface, I consider the battle between myself and this fish, between humans and nature.

Statistics compiled from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Fascinating article! Things I never knew about a sting-ray. Thank you Jesse!

Also, many innovative and life-saving medical devices require plastic.